🇮🇹 Versione italiana

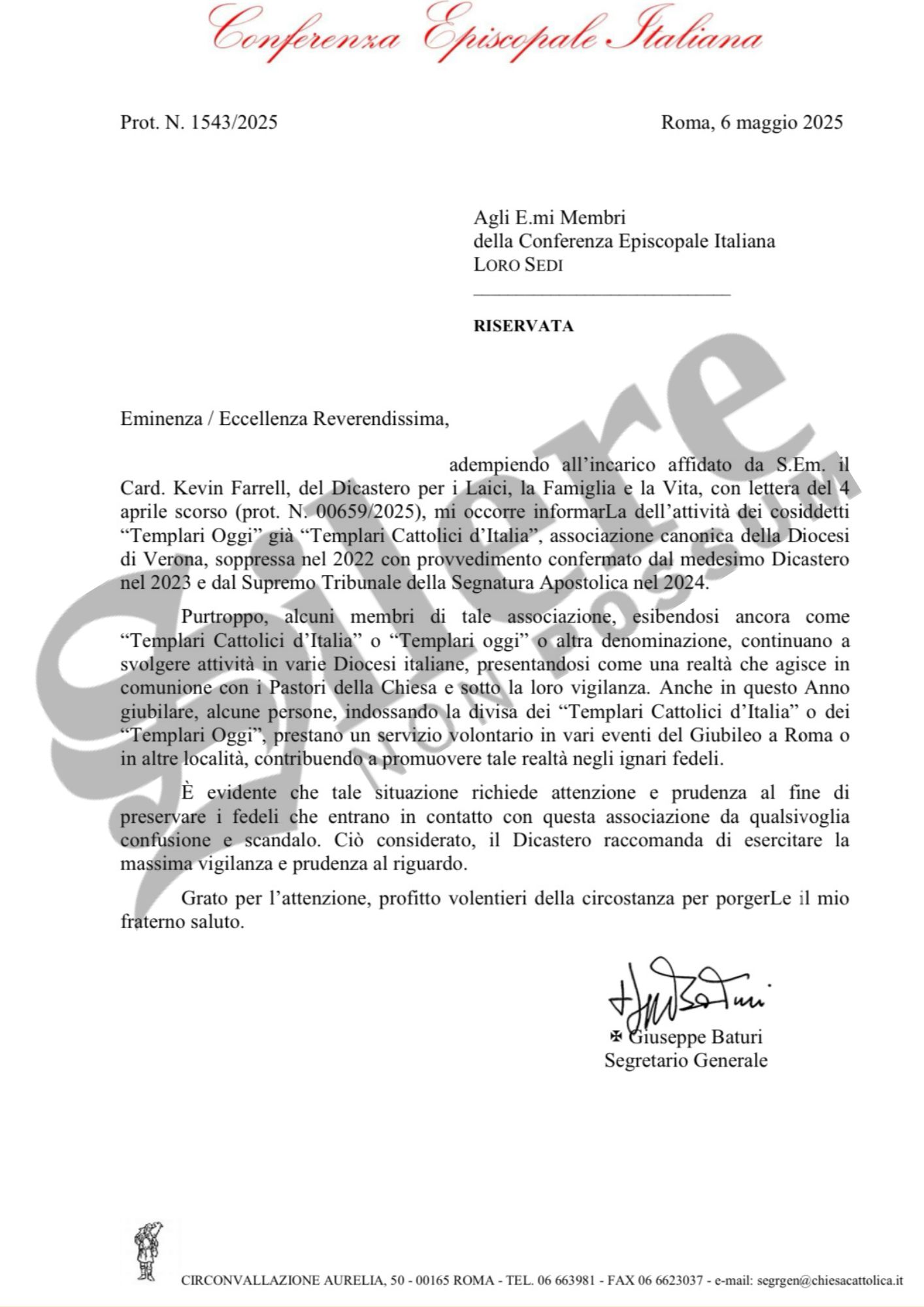

Vatican City — In recent hours, media and ecclesial attention has once again focused on the association Templari Oggi, following revelations published by Silere non possum. The controversy centers on the group’s participation in the Eucharistic celebration of 22 May in the Basilica of San Giacomo Maggiore in Bologna, presided over by Cardinal Matteo Maria Zuppi. The event would have attracted little notice were it not for an awkward coincidence: only days earlier, the Italian Episcopal Conference (CEI) — chaired by the same cardinal — circulated a confidential letter warning Italian bishops against engaging with the association.

The apparent contradiction quickly raised questions. How can an association that has been officially suppressed, and about which the Dicastery for the Laity, Family and Life deemed it necessary to urge the CEI to alert all diocesan ordinaries, be welcomed at the altar during a public liturgy presided over by the president of the CEI himself? Why has Cardinal Zuppi, at the heart of this discrepancy, felt no need to offer a public explanation? So far, these questions remain unanswered. Meanwhile, on social media the Templars have defended themselves with a flurry of posts and comments, insisting on the legitimacy of their activities and highlighting their “transparent” service to the Church.

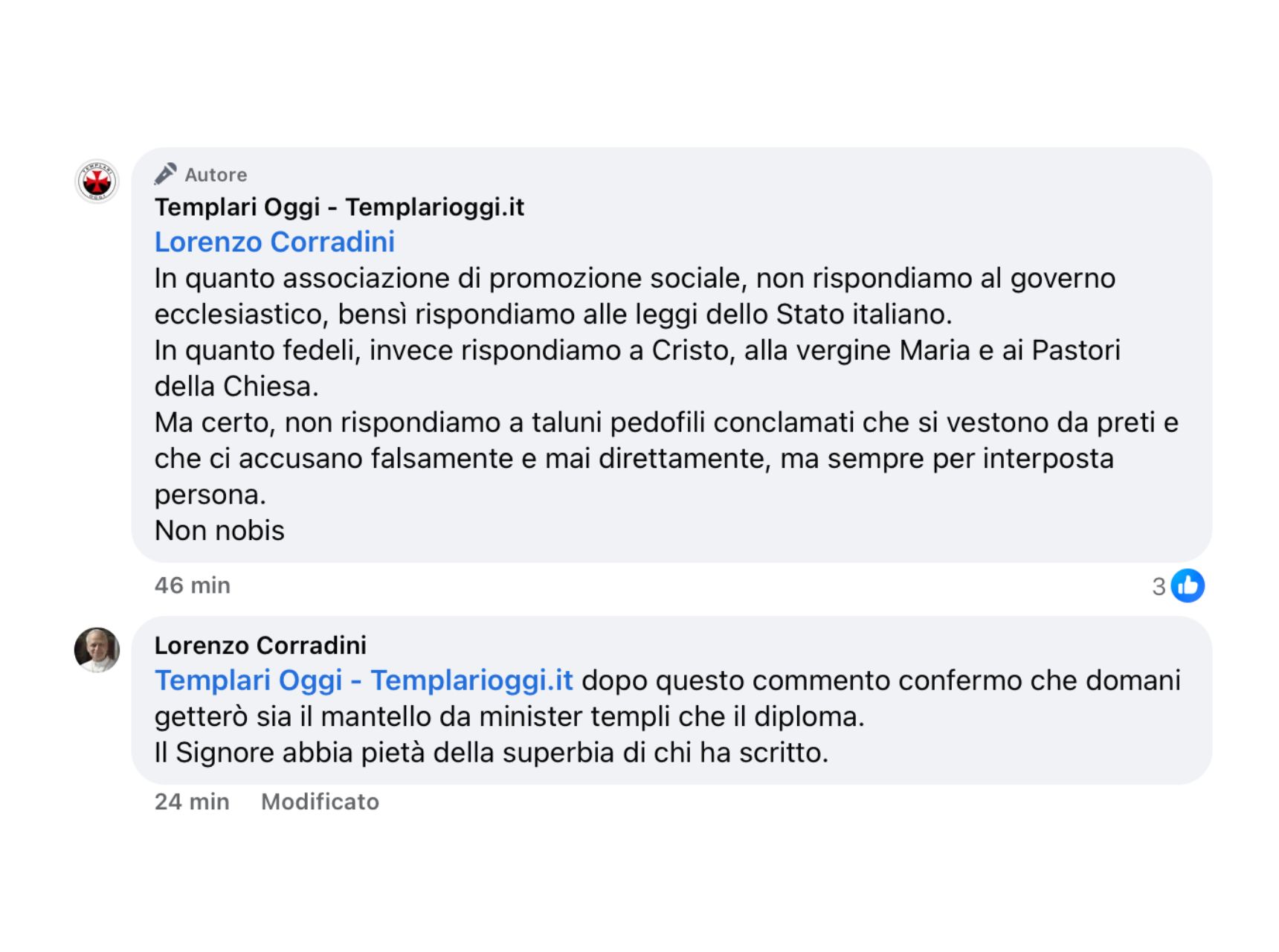

The situation, however, soon took a darker turn. Responding to criticism, the association’s official Facebook page posted a comment that caused widespread dismay: “As an association for social promotion, we are accountable not to ecclesiastical governance but to the laws of the Italian State. As the faithful, we answer to Christ, the Virgin Mary and the Shepherds of the Church. But certainly we do not answer to certain pedophiles who dress as priests and accuse us falsely, never directly but always through intermediaries.”

These harsh, offensive words overstep every boundary of respect toward Church pastors. In mounting the all-too-familiar and sterile charge of generalized pedophilia, the comment effectively defames the entire episcopate. Yet, as one Italian bishop told Silere non possum, “this confirms their modus operandi.”

Indeed, the association has previously displayed overt hostility toward ecclesiastical authority. The most emblematic case unfolded in the Diocese of Verona, where the Templars were originally erected as a private association of the faithful by Bishop Giuseppe Zenti. On 2 February 2022, however, the ordinary was compelled to suppress the Templari Cattolici d’Italia after a lengthy and complex canonical process.

The decree — examined by Silere non possum, which would gladly have done without publishing it — details how the association’s leadership consistently avoided all dialogue and oversight.

After recognizing the group in 2019 as a private association of the faithful, Bishop Zenti set up a commission to revise its statutes, citing several discrepancies between the text and the community’s actual lifestyle. The Dicastery for the Laity, Family and Life shared these concerns and urged that a canonical visitation be conducted.

At that point relations broke down completely. The visitation, meant as an opportunity for discernment and dialogue, was summarily rejected: neither the president nor the board agreed to meet the Visitor appointed by the bishop. Worse still, the Templars continued their activities in Verona despite an explicit prohibition and unilaterally moved their headquarters to Parma, openly defying the bishop’s directives. All these gestures, Bishop Zenti wrote, signaled a “firm opposition and estrangement from the guidelines given,” causing “scandal and division both within and outside the association.”

Seen in this light, the recent episode in Bologna cannot be dismissed as a mere liturgical misunderstanding. It reflects a deeper ecclesiological problem. The association claims a dual identity: on the one hand, a lay entity subject to civil law; on the other, a group of Catholic faithful active in the Church. Yet whenever the two spheres collide, the criterion adopted is never communion with the pastors but rather autonomy, accusation and self-assertion.

The Gospel, however, knows nothing of loyalty to “Christ without the Church.” Tradition — as the Second Vatican Council reminds us — teaches that whoever listens to the Church’s pastors listens to Christ himself (Lumen Gentium 20–21). To claim a Templar spirituality while disobeying ecclesial hierarchy is a contradiction in terms. Medieval knights swore loyalty and obedience to their ecclesiastical superiors; today’s Templars, by contrast, take refuge behind civil status to evade any form of oversight.

Throughout all this, Cardinal Zuppi’s silence endures. It is legitimate to ask why the president of the CEI allowed an association suppressed by a fellow bishop — and flagged by the competent Dicastery, which requested a circular letter to all ordinaries — to be publicly involved in a liturgical celebration.

Further, why, faced with precise questions, does the cardinal remain silent?

In the absence of an official explanation, unease is growing among Italian bishops and priests who daily encounter these individuals in their distinctive garb within churches. The affair once more underscores the need for serious discernment, not only regarding associative forms but also concerning how the Church administers discipline and internal communion. At stake is the very credibility of a Church called to be “one, holy, catholic and apostolic,” even in the way she deals with those who, while professing fidelity, in practice behave as a separate body.

d.T.G.

Silere non possum